When it comes to earthquake preparedness, the U.S. is surprisingly behind the times. Despite the fact that nearly half of all Americans are susceptible to potentially damaging earthquakes, the country is ill-prepared to sustain a tremor of the magnitude that scientists have warned about. Kathryn Schulz ofThe New Yorker recently reported that the odds of a disastrous earthquake occurring in the Pacific Northwest in the next 50 years are about one in three.

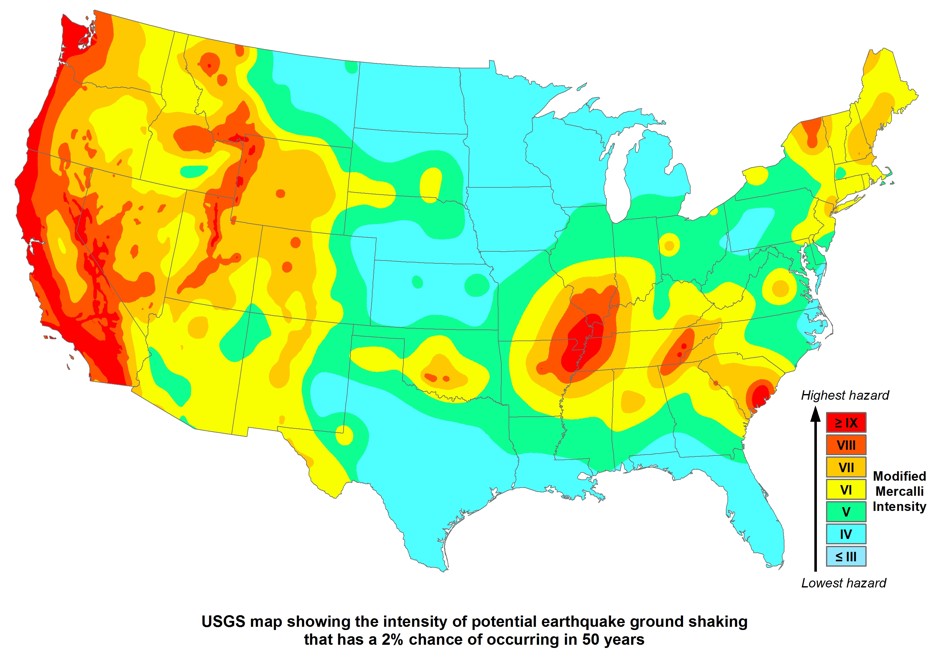

If such an earthquake were to strike, the Federal Emergency Management Agency predicts that nearly 13,000 lives would be at stake. The map below shows the potential hazard for regions around the country over this 50-year time span. Note the frightening swath of red along the West Coast, which corresponds to a nine or above on the Mercalli scale of earthquake intensity—an indicator of violent-to-extreme damage.

A critical component of preparing citizens for potential disasters is a so-called “early earthquake warning system.” While many countries including Japan, Mexico, and Romania already rely on such systems, the U.S. has been slow to implement this technology. But for the past 10 years, the U.S. Geological Survey (along with institutions like the California Institute of Technology, the University of California-Berkeley, the University of Washington, and the University of Oregon) has been developing an early warning system that would operate in high-risk states on the West Coast.

In February, at the first-ever White House Earthquake Resilience Summit, officials and researchers announced that one of the most promising seismic alert tools would be moved into beta testing—a system called ShakeAlert. The system provides residents with an earthquake warning of a few seconds to around 30 seconds, depending on the magnitude and their distance from the epicenter, so they have time to prepare.

In areas along the San Andreas fault in California, for instance, the best-case scenario would allow for a minute to a minute-and-a-half of preparation. In the Cascadia subduction zone in the Pacific Northwest, a warning could be issued up to five minutes in advance of a quake. Jennifer Strauss, the chair of the education and training committee for ShakeAlert at Berkeley, says the tool is especially critical for dense urban communities in San Francisco and Cascadia that are vulnerable to seismic damage but far enough from epicenters to take advantage of a warning.

“Those are the populations and the infrastructure that have the highest hazard and most costly impact,” she says.

How it works

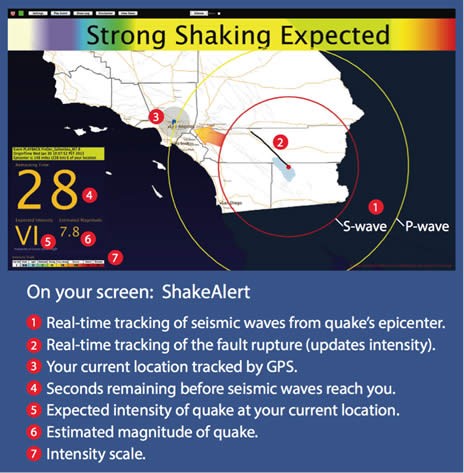

When an earthquake begins, ShakeAlert is able to detect what are known as P-waves, or compressional waves—the first seismic waves to arrive on the scene and rarely the source of any damage. This detection is made possible at the moment thanks to the California Integrated Seismic Network, which consists of 400 high-quality ground-motion sensors.

Once the detection has been made, ShakeAlert sends signals to a computer system, or “earthquake alert center,” at the speed of light. The alert center then sends a message to a user’s computer or mobile phone with the magnitude and location of the earthquake, as well as how much time remains before S-waves (or shear waves) will arrive. These S-waves are responsible for the shaking motion one experiences during an earthquake. Since they are slower than P-waves, S-waves allow for a brief period of time during which the system can warn residents of impending danger.

The following image shows what a ShakeAlert message might look like to the public. The message includes a map denoting the epicenter of the earthquake, as well as the magnitude and location of P- and S-waves.

In theory, messages like this would give people enough time to take cover, medical professionals enough time to suspend their operations, and emergency responders enough time to react to the crisis. However short it may seem, a seconds-long warning might also allow the government to shut down transportation networks and other vital forms of infrastructure like gas and electric supply lines.

Already, San Francisco’s Bay Area Rapid Transit system has partnered with the Berkeley Seismological Laboratory to gain access to ShakeAlert technology. Thanks to this partnership, BART trains now stop automatically when the system detects shaking at remote sensors, giving the train more time to slow down in the event of an earthquake. Thomas Heaton, the principal investigator of the ShakeAlert project at Cal Tech, says many other government agencies use this system as well.

Challenges to mass distribution

So what’s stopping the U.S. Geological Survey from rolling out their project on a public scale? The answer, in short, is lack of funding. Although Heaton contends that the U.S. “is probably in the lead” in terms of early earthquake warning system research, ShakeAlert is not yet ready for public consumption.

“I think all of us recognize that the current system, although much further along than it was five years ago, is still sub-optimal,” Heaton tells CityLab. “It may create more problems than it’s worth if we released all of our raw information to the public at the moment.”

Strauss echoes this sentiment. Although she contends that the project could go public about 18-24 months after full funding is achieved, the Berkeley team is intent on making sure that ShakeAlert “has consistent funding to be up and running in perpetuity.”

As of 2015, the USGS estimates that it will cost $38.3 million in capital funding to roll out the system on the West Coast, and another $16.1 million per year to keep it running. But as concern over earthquake preparedness continues to mount, ShakeAlert is getting closer and closer to achieving its goal. In December, President Obama included an $8 million allotment for an early warning system in his 2017 presidential budget plan, and Congress has already approved a $10 million budget for the project.

With the government expressing continued interest, researchers have big plans for ShakeAlert’s eventual application. “The intent is that there will be a plethora of apps that you can download to get the warning when this becomes a public system,” said Richard Allen, the Director of Berkeley’s Seismological Laboratory, at the recent White House summit. Allen also expressed a desire to connect this technology with TV, radio, and home-security systems.

The question, then, is not if ShakeAlert will be made, but whether it will be available in time for the next “big one.” When posed with this question, Heaton laughs: “Certainly, in 50 years, it better be developed by then.”

http://www.citylab.com/weather/2016/03/shakealert-earthquake-alert-warning-system-usgs-geological-survey-west-coast/472227/

No comments :

Post a Comment